6.3. Inverted Queries stored in Couchdb

6.3.1. Motivation

The direct reason to store inverted queries directly in Couchdb rather than including them in a DomeinFile (the machine-readable version of a model) is that Couchdb limits documents to 8 Mb. Models with around 1000+ lines exceed that limit. Another reason is that inverted queries are only necessary when the end user (or one of his peers) updates a resource. Instead of keeping all inverted queries in memory, we’d better fetch them from the database when needed.

6.3.2. Outline of the design

On parsing and compiling a model text, we keep the inverted queries that we construct in state (PhaseTwoState) - and do not include them in the types we’re constructing. After compiling, we fetch the array of inverted queries from state and turn them into a JSON file that we attach to the DomeinFile proper.

Then, on loading a model for the first time in an installation, we just retrieve the attachment and bulk-store all individual inverted queries as separate documents in a database to that purpose; that is, to hold the inverted queries of all loaded models.

On updating a model we first remove all inverted queries associated with that model and then repeat the same process as on first installation. There is no longer a need to modify models that are imported by the model we add (as we used to do prior to version 0.24.1).

Then, when the end user or one of his peers modifies a resource, we just query that database to retrieve the applicable inverted query descriptions. We then fall back to the original process of compiling and executing these inverted queries.

6.3.3. Keys

How to retrieve the inverted queries that are applicable, in a given situation? The prime concept to understand that question is that a query describes a path through type-space, e.g. from a role type to another role type. However, as types are described with (compound) Abstract Data Types, a single step in such a path may correspond to several paths in terms of simple types. For example: a model may provide two alternative ways to fill a role. The step from that role to its filler can be described with a SUM type as its destination; but this corresponds to two paths in terms of simple types (R → SUM F1, F2 versus R → F1, R → F2 ).

Prior to PDR version 0.24.1, inverted queries were stored with the Perspective types of the resource that is mutated. This by itself indicates that this type is part of the key that identifies a particular inverted query. In general, when a role is involved - e.g. when a role is added to or removed from a context, of when it is filled or emptied - the role-context type combination should be included in the key. From this it follows that the keys for role-filling consist of two RoleInContext combinations.

As noted above, a query is a directed path through type space. The mere combination of two RoleInContexts does, by itself, not recognise that direction. Hence we represent the keys for inverted queries that move from filled to filler with differently named fields than from filler to filled. Similar reasoning applies to the context operation (from role to context) and the role operation (from context to role).

6.3.4. Type level keys versus instance level (runtime) keys

When we deal with instances (in runtime), each resource has exactly a single base type. Keys in runtime therefore are composed of simple (non-compound) types. But as we have seen above, keys on the type level may consist of compound types. This allows us to store but a single version of an inverted query for many runtime keys - albeit with a (compound) type level key. The Couchdb views that we define to later query the inverted query database, expands a single type level key to many instance level keys. This makes querying fast.

6.3.5. Instance level key construction

6.3.5.1. Role step keys and context step keys

On adding a role to a context (and, mutatis mutandis on removing it) we should look for queries that traverse that link in type space. That will be queries with the role step, written as the type of the role. The role step takes us from a context to instances of one of its roles.

What keys should we construct to find the relevant queries? Remember that we have at hand an instance of a context and an instance of a role.

The key will consist of a context type and a RoleInContext type - that is, a compound type consisting of a context- and a role type. Now notice that we have two kinds of context here for a role: the instantiation context type in which it appears (that is, the type of the context that the instance belongs to) and the lexical context type: the type of the context that the type of the role is defined in.

First of all, we should construct a key for both context types:

| context type | role in context | key |

|---|---|---|

instantiation context C |

[role type; instantiation context] [R;C] |

C - [R;C] |

role lexical context C |

[role type; role lexical context] [R;C] |

C - [R;C] |

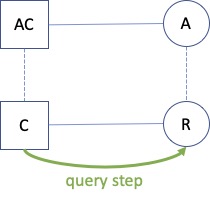

Notice that as the lexical context and the instantiation context are the same, we construct the same key twice (but this will not be so in the next case!). But we’re not done yet: we have to add, for each Aspect of the role, a key that combines the Aspect role in its lexical context with the Aspect context: AC - [A;AC]. All in all we have two keys for this situation:

-

C - [R;C]

-

AC - [A;AC]

Intuitively, both the path from C to R and the path from AC to A can be part of a query.

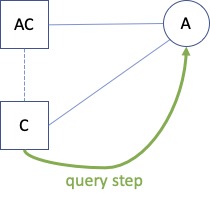

Next, consider this case, in which an Aspect role is used as is in the context instance (it is instantiated in the context instance):

Watch what happens if we apply the method outlined above:

| context type | role in context | key |

|---|---|---|

instantiation context C |

[role type; instantiation context] [A;C] |

C - [A;C] |

role lexical context AC |

[role type; role lexical context] [A;AC] |

AC - [A;AC] |

As A has no aspects, these are all the keys for this situation:

-

C - [A;C]

-

AC - [A;AC]

Intuitively, both the path from C to A and the path from AC to A can be part of a query: hence these keys.

Summary. We can simplify the above, combining the construction of keys on the role’s basic type and the construction of keys for its aspects, as follows:

-

take the transitive closure under Aspect of the role type (these are all the types of the role instance);

-

combine each into a RoleInContect with its lexical context type (find that by retrieving the type of the context from the type of the role) and then produce a key from that lexical context and this RoleInContext

-

finally, add the key constructed from the instantiation context and the RoleInContext [role type; instantiation context] (notice that this may duplicate an existing key).

Final observation. Notice that, by construction, in every key C - [R;C] both context positions will be filled with the same type. We can therefore simplify the key to C-R.

Context step keys. The role step takes us from a context to instances of one of its roles. The context step moves in the opposite direction. Obviously, on retrieving queries in runtime we should not confuse the two. But the reasoning is exactly the same. We indicate direction by using differently named fields in the keys (remember that in Couchdb the data constructors will not appear in the keys; just the objects with their fields!):

data RunTimeInvertedQueryKey =

| RTRoleKey

{ context_origin :: ContextType

, role_destination :: EnumeratedRoleType}

| RTContextKey

{ role_origin :: EnumeratedRoleType

, context_destination :: ContextType}

6.3.5.2. Filled step keys and filler step keys

Filler- and filled steps move from one role instance to another. But we have role in contexts to consider and, like with the context- and role steps, we then must use both the lexical context and the instantiation context. So, for both roles we create both role-in-context combinations (and remember that instantiation- and lexical context are the same unless we use an Aspect role as is in a context). Next, we must consider all role-in-context combinations formed by the aspect roles and their lexical contexts.

This gives us two sets of role-in-contexts: one for the filler role, one for the filled role. We then create keys for the full Cartesian Product. Not all combinations are equally likely, but any may occur.

The filled step moves in the opposite direction than the filler step. As with the context- and role step, we indicate direction by using particular field names:

data RunTimeInvertedQueryKey =

-- The filler step takes us from a filled role to its filler.

| RTFillerKey

{ filledRole_origin :: EnumeratedRoleType

, filledContext_origin :: ContextType

, fillerRole_destination :: EnumeratedRoleType

, fillerContext_destination :: ContextType}

-- The filled step takes us from a filler to the role that it fills.

-- Each combination of an element in fillerRoleInContexts with filledRoleInContext is a valid runtime key.

| RTFilledKey

{ fillerRole_origin :: EnumeratedRoleType

, fillerContext_origin :: ContextType

, filledRole_destination :: EnumeratedRoleType

, filledContext_destination :: ContextType}

6.3.5.3. Property step keys

When constructing a type level property key, there are three things to consider:

-

is the property value represented on the role instance that occurs in the path? Or is it represented on one of its fillers?

-

is the property defined on the type of the role instance that it occurs on, or is it an aspect property of that role type?

-

(if an aspect property) is a property alias used in the query?

The first two questions are independent; the third depends on the second. Let’s explore the six possibilities.

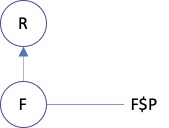

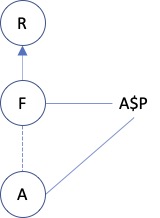

Case 1. Property P is defined on type R and the property value is represented on an instance of R. In this case, we identify the path with R$P - R.

Case 2. Property P is defined on the filler type F and the property value is represented on an instance of F. In this case, we identify the path with F$P - F. Do we also need the key F$P - R? In runtime, we derive from R its filler F and see that it is that role that actually represents the value of the property. So we generate F$P - F. How about type time? There are two cases:

-

the query we analyse is a state query. In that case, it ends with the Property step and the inversion starts with the Value2Role step. In that case, we generate the F$P - F key.

-

the query is the object of a perspective and that might be R (if it is F, we obviously should generate F$P - F anyway!). If it is R, we then construct an extended query for property P. The extension adds the binder step and that brings us to F. But then, we have in effect the same query as in the state case. Again, we find that F$P - F suffices.

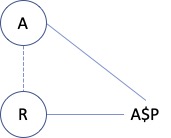

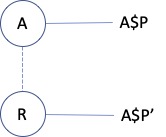

Case 3. This case sees property P defined on an Aspect role A. R uses A as aspect. The property value is represented on R. In this case, we must construct two keys:

-

A$P - R

-

A$P - A

Why? Well, two segments in type space apply to this instance situation. The obvious one is from the property to its direct role type. But since the instance is an instance of A as well, we also need the key from the property to the Aspect role.

Case 4. Here we have role R filled with F, while F has Aspect role A that contributes property P. We need the path from the Aspect property to the role that bears the property: A$P - F. Similar reasoning applies as in case 2. But we also have that the path is described by A$P - A, similar to what we had in case 3. So we need A$P - A as well. In total:

-

A$P - F

-

A$P - A

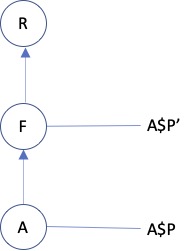

Case 5. The fifth scenario sees an aspect property contributed by role A, represented on role R. However, instead of using its original name P (as defined on A), an alias P' is used. In this case we want two keys:

-

A$P' - R

-

A$P - A

The first case covers the segment in type space that runs from the property alias to the role on which the value has been represented - it corresponds directly to what must have been the query step. The second case is the type space segment from the Aspect role to the (original) Aspect property.

Case 6. Finally, the sixth and last case sees a property on the filler role, contributed by Aspect role A, but used with an alias. This is similar to case 5, but now an aspect property is used on the filler and thus we need:

-

A$P' - F

We als need the description from the Aspect to its property under its own name, like with case 5:

-

A$P - A

6.3.6. Type level keys

At first sight, one might think we do not have the instantiation context when analyzing, for example, the role step of a query. But actually, the query function description of that step has a RoleInContext combination as range type. And the context in that combination is exactly the instantiation context type - even when the role type is an aspect role. This opens up the possibility to compute, in compile time, the same keys as we can compute in runtime (albeit probably a larger set).

So we construct the very same keys in compilation time and package them with the inverted query. Later, when we add each inverted query as a separate document to the inverted query database, the view function emits all of these keys for the same query.

Constructing them in compile time is slightly different from constructing them in runtime. Let’s outline the general idea for the case of the context step. The domain of that step is an ADT RoleInContext. Now, the ADT may be a single RoleInContext, or it might be a compound type consisting of SUMs and PRODUCTs. For the runtime situation, we have an algorithm to construct from a single combination of role and context type an array of keys (outlined above). Let’s call the corresponding function roleContextCombinations. The approach for the compile time computation must be a generalization to the full ADT. We’ll proceed as follows:

-

traverse the ADT with

roleContextCombinations -

collect all leaves in the ADT (now being Arrays of role-context combinations)

-

flatten the result and construct keys from each combination.

Why is it semantically sound to just collect all leaves? Let’s consider the two complex cases apart.

For a SUM type, the members are alternatives. In runtime, each of these may occur. Hence, in compile time, we have to prepare all keys; so we can just append all member arrays.

A PRODUCT type represents either the Aspects of a Role, or its filler. Fillers are of no issue here, so it’s about Aspects. The algorithm for the basic case just collects all keys derived from Aspects - and so we will do the same with keys that derive from members of a PRODUCT type.

6.3.7. The shape of the keys

Couchdb allows keys to be Javascript objects. As our keys are records on the Purescript level that let themselves be read as Javascript objects, it seems straightforward to use this representation as values for keys of Couchdb documents that represent Inverted queries. However, the key must be marshalled as a html query parameter to couchdb and this involves serialising and de-serialising. It then turns out that:

-

the order of the fields seems to matter;

-

some characters in our identifiers (particulartly the hash (#) sign) must be escaped to be included in the query parameter value.

This makes the use of the object representation of keys brittle. I have not been able to find out how Pouchdb serializes objects; neither is clear to me whether Couchdb first deserializes such a query parameter value and only then compares it to the javascript object keys, or whether it serialises the keys and then compares it to the query parameter value. And what about the keys that are generated on constructing a view? Are they in string form, maybe, in the B-trees that represent the views?

All in all I’ve decided to derive a string value from the Purescript records that represent query keys and to include those values in the documents that we store in Couchdb. We bypass the entire issue sketched above and this works as expected.