15.1. Synchronisation

Because the Perspectives Runtime is a distributed system, we have to find a way to make state changes initiated by a user available to peers who share a perspective on the changed entity. We call that process synchronisation. In this text we explore some technical issues.

Users are the only source of state changes. A user can initiate changes through some client program that will communicate his intentions to the PDR. This client-PDR communication does not concern us here, but the Perspectives Application Program Interface (API, the module Perspectives.Api) is a good starting point for our exploration. Why? Because here we find top level functions that can be invoked by the user to change state.

In principle, if we could make the PDR of peers invoke the very same functions with the same arguments, they would change their state in the same way and we would have synchronised their local representation of Perspectives State. We might call this a remote procedure call mechanism (RPC).

Of course, not every change a user makes is relevant for all his peers. A peer should only be informed if he has a perspective on the changed entity. The PDR finds out by consulting the model and reflecting that on the instances and users at hand.

The bulk of this text is devoted to this RPC mechanism.

It is noteworthy that there is another starting point for our exploration and that is the language in which a modeller can write actions to be executed on state change. By writing such actions, the modeller automates some user actions (in a specific role). In principle, exactly the same functions for changing state can be used in automatic actions as in user actions. So we could take the module that implements the semantics of the language keywords for actions as a second starting point for our exploration: Perspectives.Actions.

There also is another mechanism by which PDRs can synchronise state and that is by sending an invitation by mail (or another manual transport mechanism). An invitation is the JSON serialisation of a number of contexts and roles. By dropping such a document on the Perspectives client program screen, the user instructs his PDR to add these contexts and roles to his local cache and store. This synchronises state with respect to the invitation between sender and receiver. This mechanism is of no importance to this text.

This mechanism is to be used by users who are not yet connected through Perspectives. It is the mechanism by which they become peers in at least a single context

Finally, we mention a last mechanism that is supported by the PDR by which state can be changed and that is loading and parsing a file with text written in the Context Role Language (CRL). Such a text, not surprisingly, describes instances of roles and contexts. Loading such a file contributes these instances directly to the cache and database. However, the end user has no means of calling the relevant functions. They exist mostly for testing purposes and for modellers. A model describes types, but must be complemented by a small number of instances (among them a context instance that describes the model; it is used by repositories to present an inventory of available models).

We will now turn our attention to the question: what is in a remote procedure call?

15.1.1. What procedures to call?

It turns out that all functions that lead to state change are contained in just three modules:

-

Perspectives.Instances.Builders

-

Perspectives.Assignment.Update

-

Perspectives.SaveUserData

Perspectives is written in Purescript, a functional language. So strictly speaking we just have pure functions. Nevertheless, there are mechanisms to handle side effects like storing information in a database. In this text we will use the word ‘function’ too, when such side effects are sorted, not bothering to distinguish them from statements and procedures.

However, some of these functions call others in the same set of modules. Obviously we want to restrict the RPC mechanism to ‘top level’ functions, to minimise the number of calls. We’ll call the RPC functions DeltaFunctions, in honour of the fact that they should add a Delta to a Transaction (Transactions are the unit of shipping synchronisation information between PDRs). A Delta mostly is the ‘serialised’ application of a DeltaFunction to some arguments, but contains a little more information that need not concern us here (such as ordering information and a list of users for whom the Delta is important).

So all functions in these three modules are candidate DeltaFunctions. We have two criteria for a real DeltaFunction:

-

It should be used in either the Api or the Actions module, and then either

-

directly, meaning that it is the implementation of the request sent by the user through the client program, or:

-

indirectly, meaning that it is used in the implementation of handling such a request.

-

-

It should not have a Context- or Role JSON serialization as argument.

To explain the latter requirement: the client program can send a JSON fragment to the API when it wants to construct a context or role instance. However, we don’t want to include such fragments in Deltas because we’d have to specialise them for each peer. As we already have a mechanism in place to select relevant peers per elementary state change, we stick to Deltas with just such elementary changes.

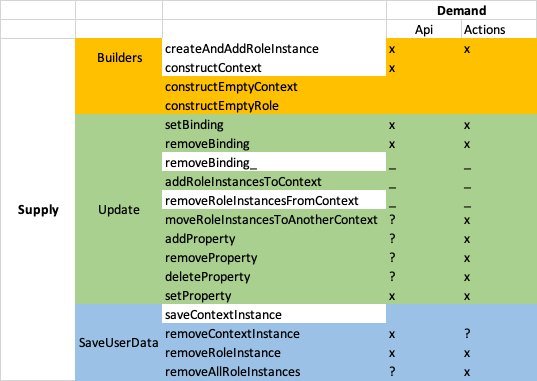

Figure 1 shows what state changing functions are available and whether they are used in the Api or the Actions module.

Figure 1 State change function supplying- and demanding modules. An x marks the usage of a function in the current implementation; a ? indicates that it will be used in the final implementation. Functions with a colored (non-white) background are DeltaFunctions.

15.1.2. Types of Deltas

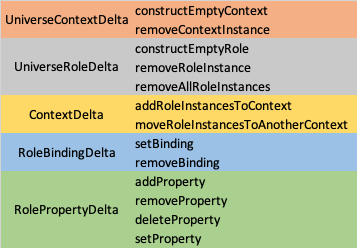

We group the DeltaFunctions in five categories, each described by a type of Delta. Some Delta members have a Maybe type if at least one function in the corresponding category has no parameter that binds that member while others do (this allows us to minimize the number of Delta types). Figure 2 gives an overview.

The ‘Universe’ Deltas deal with creation and annihilation of context- and role instances.

The ContextDelta deals with adding or removing role instances to or from a context instance.

The RoleBindingDelta and RolePropertyDelta deal with the two ways to change a role instance.

Figure 2. Delta types and Delta functions.

15.1.3. Executing Deltas

On receiving a Delta, the PDR executes the function it specifies, applying it to values of the Delta members according to a fixed member-parameter mapping worked out in the source code.

Deltas are shipped in Transactions. It is important to execute Deltas in the same order as in which the DeltaFunctions were executed by the sender of the Transaction. One cannot, for example, add a Role instance to a Context instance before both are created! This order is preserved in the member sequenceNumber that is in each Delta (we cannot simply compile an ordered list of Deltas, because Purescript collections have to be homogeneous).

The DeltaFunctions are monadic. Their monad is MonadPerspectivesTransaction. Applying runMonadPerspectivesTransaction to the application of a DeltaFunction will actually effect the state change. It will, too, trigger state changes and update queries.

The sending PDR runs a value in MonadPerspectivesTransaction such that Transactions are actually distributed to peers. However, when a Transaction is run in the receiving PDR, state changes are triggered and queries updated, but no Transactions are distributed.

15.1.4. Declarative versus procedural synchronization

Synchronization by remote procedure call is not a very declarative mechanism. We rely on re-executing the original instructions in another PDR to reconstruct the relevant parts of state. Instead, we could try to send a full description of changed data.

While this would be of some interest, it would also be much more verbose. Also, it cannot be complete. This is because users have different perspectives. As a consequence, a particular role instance may be the binding of another role for some users but not for others. So we cannot put that information in a Delta. It would be indiscrete, as a user would send information on binder roles to a peer who did not even know of their existence; and it would be incomplete, as the user has no way of knowing the entire set of binders for a particular role according to the perspective of a peer.

We have two use cases for this kind of delta. First, such Deltas could be used for an undo mechanism (particularly for deleting entities). Second, a collection of such Deltas would be a valuable base for machine learning or user statistics.]

Interestingly, peers that share a perspective on a role always have the same set of role instances for a particular context instance. We have no ‘conditional’ perspective, where the ability to see a role instance depends on that role’s property values or binding.

To prevent misunderstanding: we do have calculated roles, that allow filtering based on property values and binding. The set of instances for such a calculated role might be different for each peer. However, the base enumerated set of unfiltered instances is always the same for each peer.

15.1.5. Design considerations per DeltaFunction

15.1.5.1. CreateEmptyRole

Conceptually we want to create a UniverseRoleDelta in the function createEmptyRole. We should compute the users that should receive this delta.

There are several reasons why we don’t want to compute these users when we construct the empty role. For one, if we construct multiple instances (in constructContext), we don’t want to recompute the users for each of them (the result would always be the same). Second, they are the same users as that should receive the ContextDelta that describes how the new role instance(s) should be added to its context instance. But we need but a single ContextDelta for all instances of a role, so we don’t want to create this delta in createEmptyRole.

So instead we compute the users in a function addRoleInstancesToContext and we have that function add the deltas to the transaction. As createAndAddRoleInstance and constructContext are the only functions to call createEmptyRole and both call addRoleInstancesToContext, we have covered all cases.

15.1.5.2. RemoveRoleInstance, removeAllRoleInstances

The DeltaFunction removeRoleInstance (Perspectives.SaveUserData) should add a ContextDelta to the current Transaction and so should removeAllRoleInstances. We’ve refactored the common functionality into an update function removeRoleInstancesFromContext (module Perspectives.Assignment.Update). It is this function that actually adds a ContextDelta, and a UniverseRoleDelta.

Roles are removed, too, when the containing context instance is removed. However, we don’t need – even don’t want – ContextDeltas or UniverseRoleDeltas in this case. The receiving PDR can work out by itself what role instances to remove.

On the other hand, we do need queries to be updated in all cases, taking into consideration the binders of the roles that were removed. We share the implementation of this process with the function addCorrelationIdentifiersToTransactie.

Similarly, we want state changes to be triggered, so we want to know all contexts that have a bot role with a perspective on the removed role.

Finally, for synchronization we need all users that should receive the Deltas. These are users in the same contexts that we needed to trigger state changes. It turns out that it is more efficient to compute contexts and users in a single process. This is implemented in the function usersWithPerspectiveOnRoleInstance. It returns the users and adds the contexts to the underlying Transaction.